Inside the Survival Brain: Helping Children Move From Chaos to Calm

“Calm down.” “Sit still.” “Stop crying.” “Take a deep breath.” Most of us have heard these instructions at some point, and many of us have said them to children in moments of overwhelm. Yet when a child is dysregulated, these phrases often feel impossible to follow. Understanding what happens in a child’s nervous system during these moments can help us support them far more effectively.

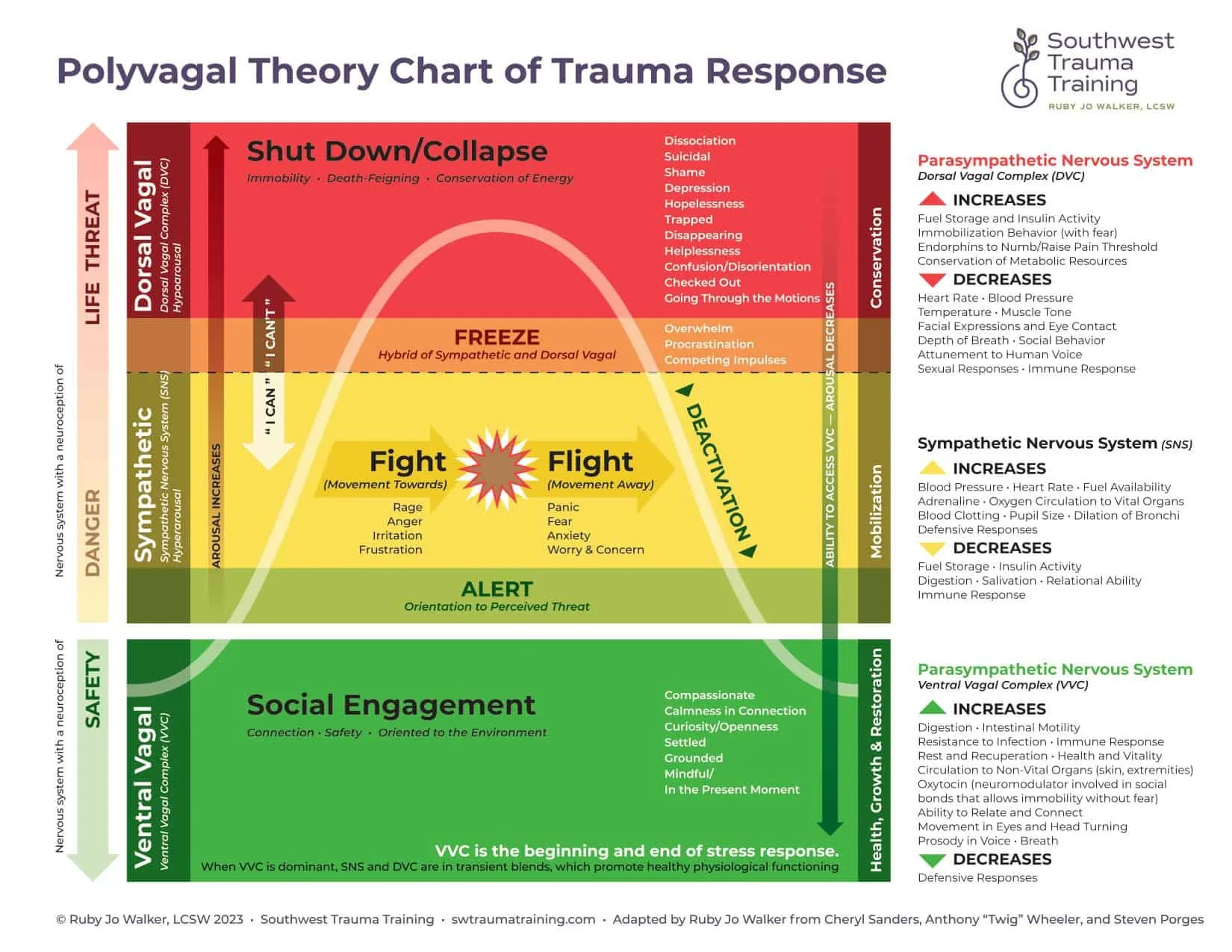

Polyvagal Theory, although far more complex than can be fully captured here, gives us a useful way to understand the internal shifts that occur when a child moves away from regulation. When a child is calm – what we might call in their “upstairs brain” - they can communicate, stay curious, be compassionate, and remain connected to the present moment. Their internal system is balanced, and this is reflected in their behaviour.

As they become dysregulated, however, they move into their “downstairs brain,” or survival brain, where automatic physiological changes begin to take over. These changes, while invisible to the eye, quickly appear as external behaviours that are often misunderstood. When a child senses a threat, whether real or perceived, the amygdala steps in to determine the level of danger. For children who have experienced ongoing or developmental trauma, the amygdala is often enlarged and hypersensitive, constantly scanning for danger even when none is visible to others. As a result, almost any challenge can feel like a genuine threat.

If the threat feels manageable, the child enters fight or flight. Heart rate rises, blood pressure increases, and blood flows to large muscles as the body prepares to defend or escape. A child in this state may seem reactive, oppositional, or controlling, but it is important to remember they are not choosing to behave this way – they are trying to survive. If escape feels impossible, the child moves into freeze. Here, the system shuts down, sensory experience becomes muted, and the child may appear passive, withdrawn, or unreachable. This is not defiance or avoidance but a biological survival response.

In these states, telling a child to “calm down,” “listen,” or “use your words” simply cannot work because the part of the brain capable of reasoning is temporarily offline. They are not ignoring us; they are physiologically unable to process what we’re saying. Regulation means helping the child return to a balanced state where they feel safe, connected, and grounded – but this can be particularly challenging when the nervous system has become accustomed to activation. The most important starting point is co-regulation. Children learn to regulate because we lend them our calm.

Co-regulation involves staying present, steady, and attuned, even when the child cannot be. Depending on the child and the moment, this may involve staying nearby without overwhelming them, considering our voice, facial expressions and body language. Sometimes movement is essential, especially when adrenaline is high: pushing against a wall, hitting a cushion, bouncing on a trampoline, throwing or kicking a ball, or rocking if a swing is available. The aim is not necessarily to stop the behaviour but to help the nervous system gradually find its way back to safety. Of course, staying regulated ourselves while supporting a dysregulated child is incredibly difficult. We will get it wrong. We will feel frustrated or overwhelmed. The child may reject our support or push us away. But rupture is not failure. Repair is where trust deepens. Each time we return, reconnect, and try again, we strengthen the relationship and communicate, “I may get it wrong, but I am here, and I will keep trying with you.”

Download PDF here